- Thu. Apr 25th, 2024

Latest Post

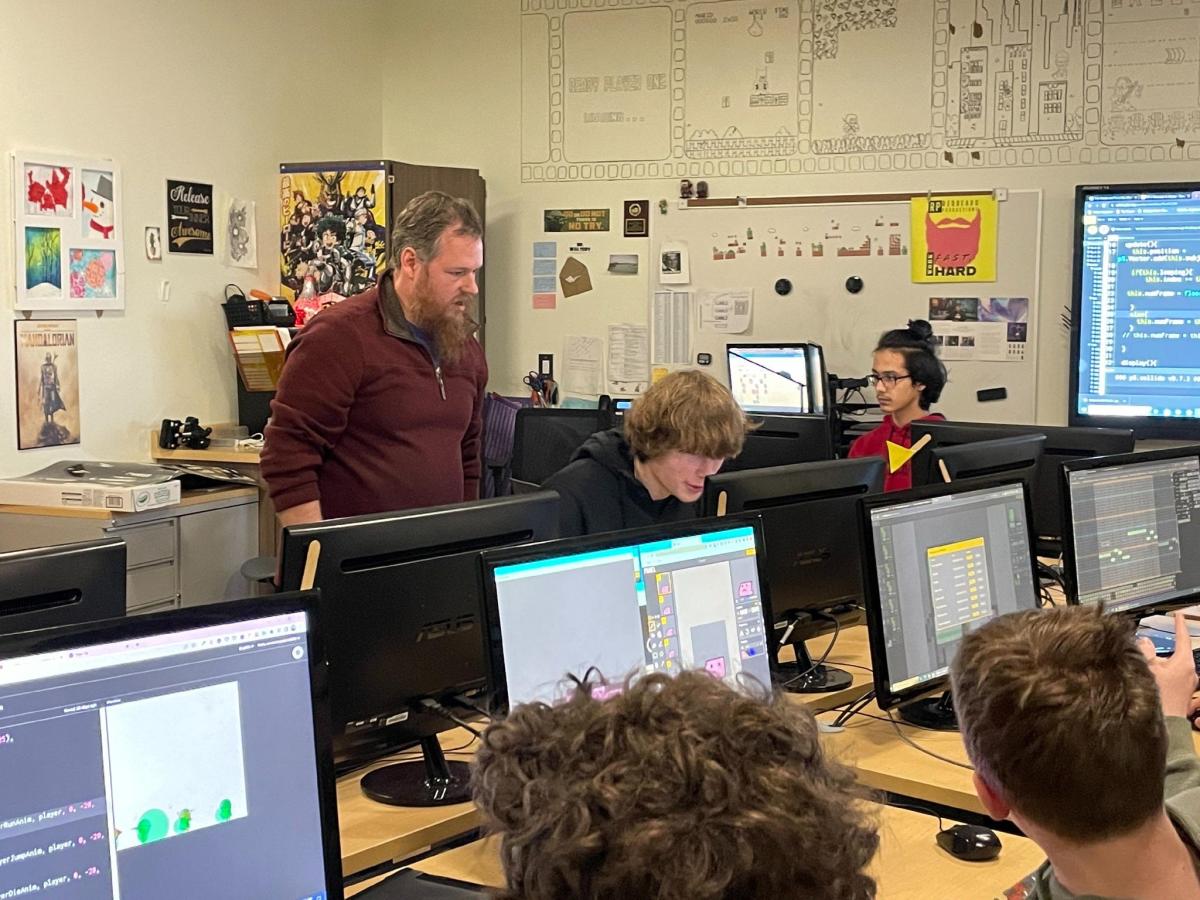

Providing Valuable Work Experience: Licking Heights Local Schools Launch High School Tech Internship Program Funded by Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation

The High School Tech Internship program, funded by an investment from the Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation, will provide real-life experience and on-the-job technology training for 10 high school students…

From Home Run to Movie Love: Kiah Helget’s Favorite Things

Kiah Helget, a senior at New Ulm Cathedral, hit a two-run home run against Nicollet on Monday at Harman Park, leading the Greyhounds to a 16-0 victory in just four…

Kidnapped Journalist Speaks in New Video Amid Ongoing Middle Eastern Crisis

On October 7th, 2023, Hirsch Goldberg-Polin, a dual citizen of Israel and the United States, was kidnapped by Hamas militants. This event took place on what is known as Black…

Exploring the Potential of RFID Technology in Retail: A Report from the RetailTech Series

RFID technology offers more than just inventory accuracy in the retail industry, as explored in this report as part of our RetailTech series. The report delves into the developments, insights,…

World Malaria Day 2021: Accelerating the Fight for a More Equitable World by Spreading Awareness and Encouraging Proactive Measures

World Malaria Day is an annual observance held on April 25th to raise awareness about the serious mosquito-borne illness. The theme for this year is “Accelerating the fight against malaria…

Bridging the Gap: Tackling Health Disparities in the Fight Against Malaria

The year 2024 marks the fifteenth celebration of World Malaria Day, an initiative launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2007 to raise awareness about the deadly mosquito-borne illness.…

AI in Law Enforcement and Court Systems: Balancing Accountability with Human Rights

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in technology, law enforcement, and court systems has raised several questions about accountability and the application of human rights to autonomous intelligences. The challenge…

Arkansas Educator Jessica Culver Selected for Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship to Explore Alaska’s Wilderness

Jessica Culver, a doctoral student in the College of Education and Health Professions Adult and Lifelong Learning program, has been chosen to participate in the 2024 Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship program.…

Blossoming Science: Beatrice High School Hosts Annual Spring Plant Sale to Nurture Future Scientists

The Beatrice High School science club is hosting its annual spring sale this week. This event, which takes place in the school’s greenhouse, has been a project initiated several years…

The World Beer Cup Awards: Where Peer Review Meets International Recognition

The 2024 World Beer Cup awards were held at The Venetian Las Vegas on April 24th, celebrating brewing excellence on an international scale. This competition, organized by the Brewers Association,…