- Wed. Apr 24th, 2024

Latest Post

Saudi Arabia’s Tech Ambitions Soar with the Launch of UK Hub, Aiming to Diversify Beyond Oil

Saudi Arabia’s regulatory reforms have led to growth in its businesses, and many are now looking to adopt new technologies. The United Kingdom, with a tech market valued at over…

Unraveling Reality: Blake Crouch’s Dark Matter and the Intersection of Science and Storytelling

As a successful author known for his mind-bending narratives, Blake Crouch had a knack for creating immersive worlds that transported readers to different realities. However, amidst his professional success, he…

RDU Plane Crash Prompts Immediate Response from UNC Health: What We Know So Far

RDU experienced a small plane crash that resulted in two injuries, prompting UNC Health to send both a physician and pilot to the hospital. According to Broadcastify radio traffic, the…

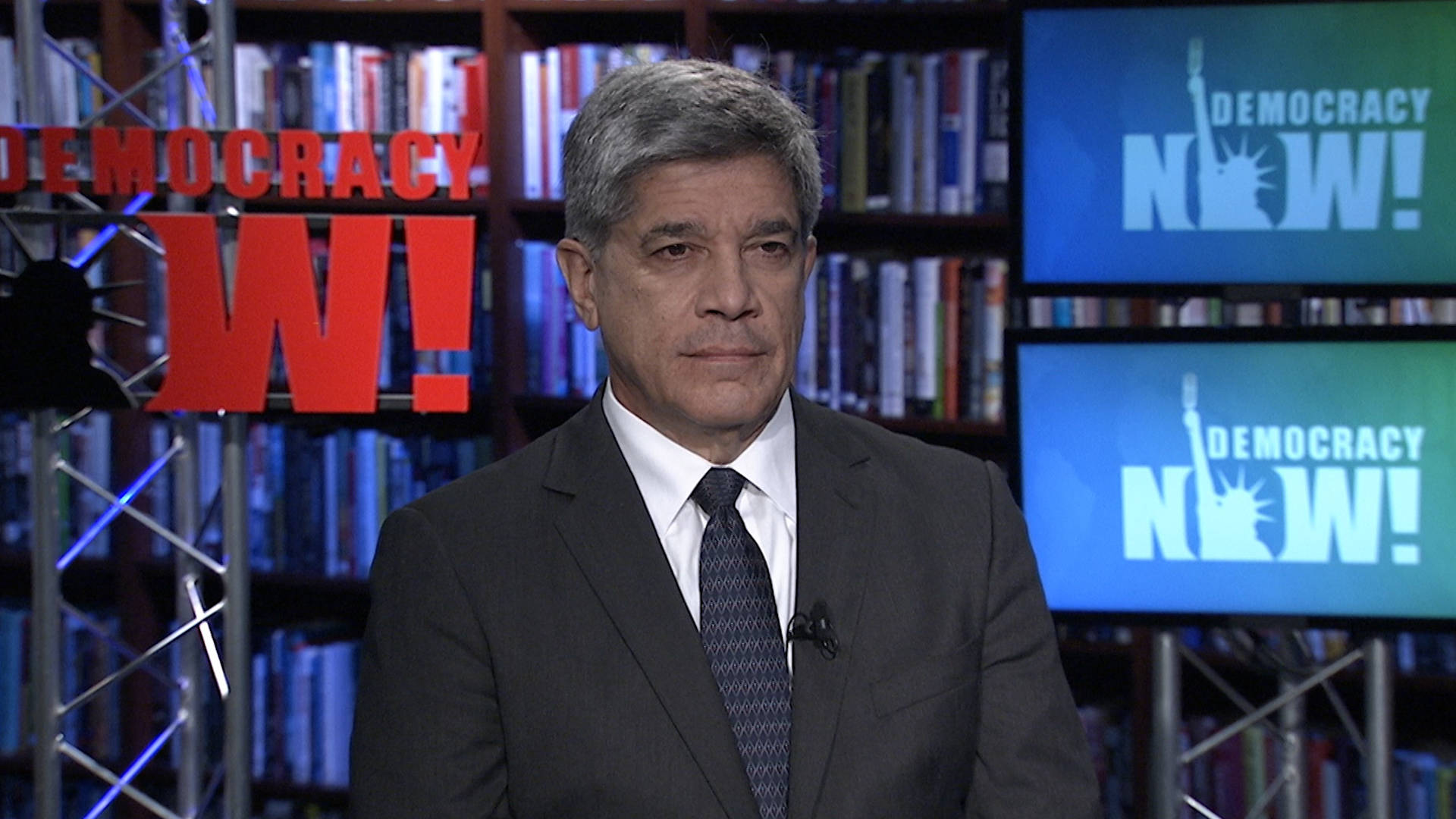

Carlos Fernandez de Cossio on U.S.-Cuban Relations: A Complex Dance of Migration, Geopolitical Conflicts, and Domestic Challenges

During our exclusive interview with Carlos Fernández de Cossío, Cuba’s deputy minister of foreign affairs, we delved into the latest developments in U.S.-Cuban relations. One of the main topics discussed…

Canton’s Fresh Produce Mandate Sparks Debate about Government Overreach in Business Regulation

Canton recently issued a directive to economy stores mandating that they sell fresh produce. This decision has sparked debate and raised questions about government overreach in regulating businesses. Many believe…

Rising Dangers of Counterfeit Botox: 22 Reported Cases Lead to Hospitalization and Potential Botulism Outbreak

Botox injections have been found to be counterfeit, leading to illness for 22 individuals. Of those affected, half were hospitalized and the cases were reported by the Centers for Disease…

BIS Certification Program Grads Heather Smith and Brook Lindsay Ready to Take on the World

Heather Smith and Brook Lindsay have recently graduated from the Business and Industry Services (BIS) Certification Program offered by Pioneer Technology Center. This program is designed to provide professional development…

Abortion Access in America: State Battles for Reproductive Rights, the Impact of President Biden and Trump on Abortion Legislation, and The Rise of Abortion Pills

In the United States, access to abortion and reproductive rights are closely monitored, especially since the Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade. The legality of abortion has been left…

From Kitchen Mix to Thriving Business: Miami University Graduate VaLandria Smith-Lash Tackles Skin Illness with Coarse Culture

Miami University graduate VaLandria Smith-Lash took action to address a dangerous skin illness by starting her own skin care business. Her dedication to creating a product that would benefit not…

Revolutionizing Technology and Future Careers: The Launch of the Siebel School of Computing & Data Science at the University of Illinois

The Siebel School of Computing & Data Science at the University of Illinois is poised to shape the future of technology and prepare students for success in a digital world.…