- Wed. Apr 24th, 2024

Latest Post

Suncoast Career Academy: Combatting Healthcare Staffing Shortage with Hands-on Training

Suncoast Community Health Centers has recently opened the Suncoast Career Academy, a new training center in Brandon aimed at combatting the shortage of healthcare staffing in the area. The non-profit…

Metsä Board invests in the future of cardboard production with EUR 60 million folding carton machine renovation

Metsä Board, a subsidiary of the Metsä Group, has announced an investment in the renovation of a folding carton machine located in Simpele as part of a larger investment program.…

AMC Theatres Appoints Stephanie Tierney as Vice President of Distribution, Unveiling Exciting New Business Ventures in Music Industry

AMC Theatres has appointed Stephanie Tierney as Vice President of distribution, following the success of their recent music events like Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour and Renaissance: A Film By Beyoncé.…

Align Technology Inc. Surpasses Analyst Expectations and Achieves Several Milestones in Q1 2024

Align Technology, Inc. recently announced strong financial results for the first quarter of 2024, leading to a 9% increase in its stock price. The company surpassed analyst expectations with an…

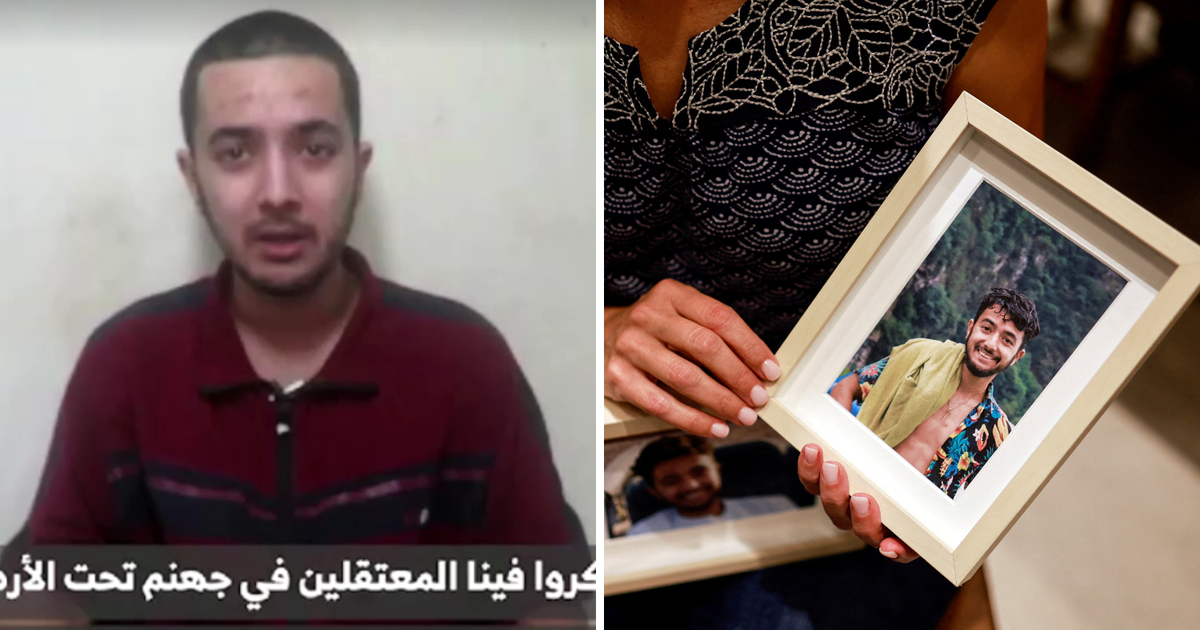

Tech Journalist Taken Hostage by Hamas: Hersh Goldberg-Polin’s Story of Courage and Resilience Amid Adversity

Hersh Goldberg-Polin, an Israeli-American with a passion for technology, was abducted on October 7th during the Hamas attack on Israel. At the time of his kidnapping, he was gravely injured…

Egypt Boosts Strategic Reserves of Essential Commodities to Ensure Market Stability

In Cairo, the Minister of Supply and Internal Trade, Dr. Ali Al-Moselhi, has announced plans to increase the strategic reserve of essential commodities. During a meeting chaired by Prime Minister…

IDF and Egyptian Intelligence Discuss Security Scenarios in Rafah

On April 24, Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) Chief of Staff Herzi A-Levi and Shin Bet head Ronen Bar visited Cairo to meet with the head of Egyptian intelligence, Abbas Kamal.…

New Jersey Court Ruling Holds Employers Accountable for Negligent Covid-19 Safety Measures in Healthcare Settings

The New Jersey Superior Court Appellate Division has ruled that the relatives of two married hospital workers who died from Covid-19 can bring a lawsuit against their employers. The workers…

The Pros and Cons of the Tiktok Ban: A Targeted Approach to Addressing Concerns About Chinese Influence and Mental Health

The US Congress is considering taking a harsh measure against the popular video platform Tiktok by forcing a change of ownership in order to reduce Chinese influence in the country.…

Beauty Salon in Bournemouth, UK: Expert Botulinum and Dermal Filler Treatments

In Bournemouth, Dorset, UK, a beauty salon named TreatMyWrinkles offers expert services in botulinum and dermal filler treatments. They specialize in these procedures and are known for their expertise in…